Scrapling: A Complete Hands-On Guide

Let's discover Scrapling, the Python library that makes web scraping easy and effortless—with practical examples!

Scrapling isn’t just another Python web data parsing library. Instead, it’s a complete all-in-one solution built to overcome the long-standing challenges in web scraping, such as rapidly changing website structures, unstable selectors, increasingly complex anti-bot measures, extreme website diversity, and pagination variations. All of that without AI, meaning it’s completely free to use!

Follow this full walkthrough to discover what Scrapling is, how it works, its features, and whether it lives up to the expectations!

Before proceeding, let me thank Decodo, the platinum partner of the month. They’ve just launched a new promotion for the Advanced Scraping API, and you can now use code SCRAPE30 to get 30% off your first purchase.

A Comprehensive Introduction to Scrapling

Let me introduce you to the world of Scrapling, so you can understand why it’s a special web scraping library.

What Is Scrapling?

Scrapling is an undetectable, flexible, and high-performance Python library that aims to make scraping as easy as it should be. It’s developed in Python by D4Vinci—the nickname of Karim Shoair, one of our fellow readers.

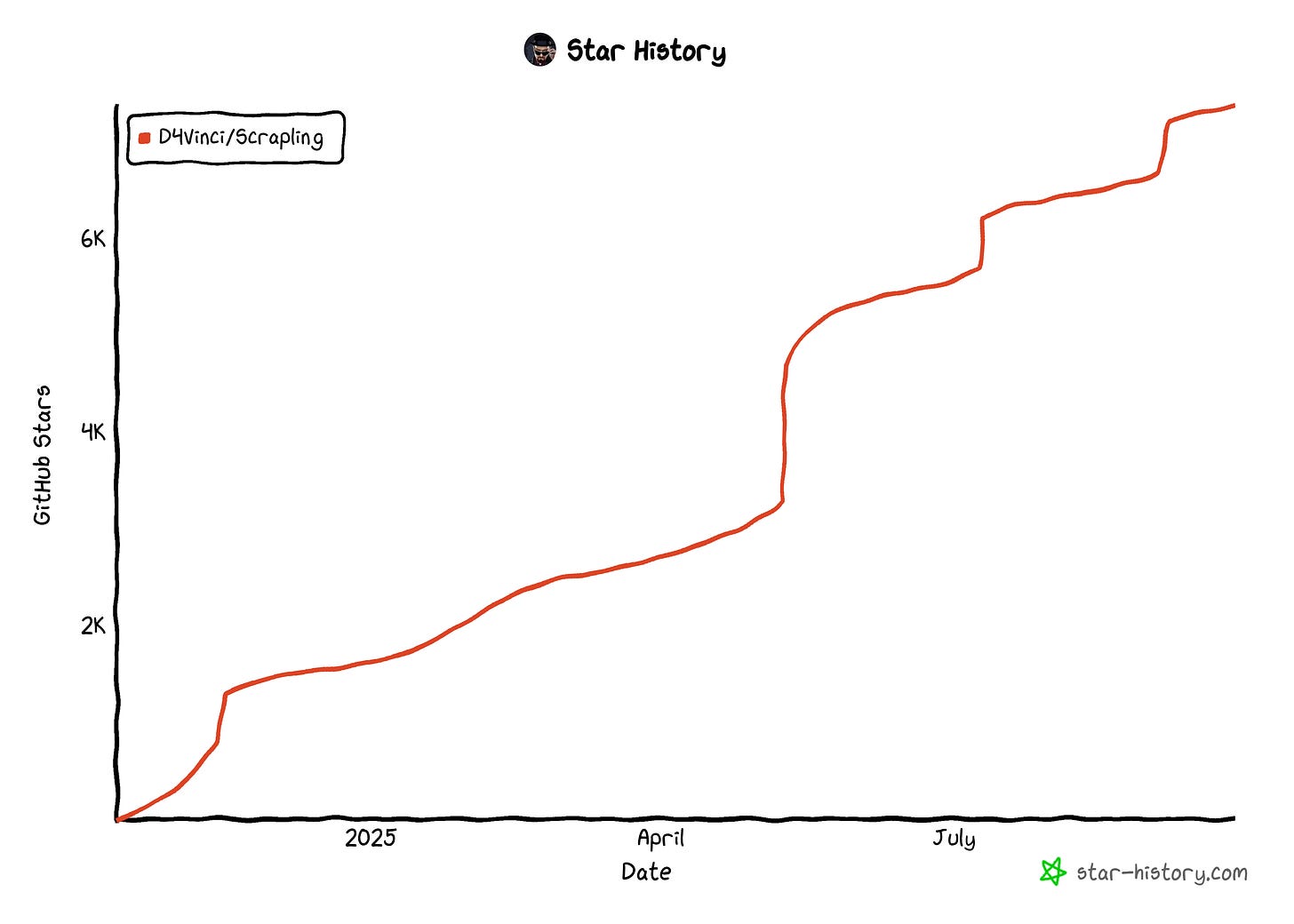

The library has already earned over 7.4k stars on GitHub, and its growth isn’t slowing down:

What sets this web scraping library apart is its speed, low memory footprint, rich feature set, and adaptive design. Most libraries break the moment a website changes its structure, but Scrapling can automatically adjust—relocating elements and keeping your scrapers running. (You’ll find more details about this mechanism in the FAQ section at the end.) And that’s just one of the many reasons it shines!

On top of that, Scrapling can bypass many anti-bot defenses, making it ideal for tackling the challenges of the modern Web.

Note: As of this writing, the latest version is v0.3.7. Version v0.3 represented the most significant update in the project’s history, featuring a complete architectural rewrite and numerous other improvements.

Main Features

Scrapling provides several features, but the most important ones you should be aware of are:

Stealthy HTTP requests with browser TLS fingerprinting, HTTP/3 support, and persistent sessions.

Full browser automation with Playwright’s Chromium, real Chrome, and a custom stealth mode.

Modified Firefox with fingerprint spoofing, capable of bypassing Cloudflare Turnstile.

Persistent sessions to maintain cookies, headers, and authentication across requests.

Smart element tracking that automatically relocates elements after site changes.

Support for CSS and XPath selectors, plus regex, text, and filter-based search options.

Interactive IPython shell and cURL-to-Scrapling conversion.

API similar to Scrapy/BeautifulSoup, with support for advanced DOM traversal and more.

92% test coverage, full type hints, and proven daily use by hundreds of scrapers.

What Makes Scrapling Special

In particular, the four main aspects that characterize Scrapling and make it stand out over other Python web scraping libraries are:

Incredible speed, with benchmarks showing it can be up to 1,735× faster than BeautifulSoup. For example, it takes an approach similar to the AutoScraper library—but with more features—and while achieving 5.4× faster results with fewer resources. It also includes a custom parsing engine for JSON serialization, which is 10× faster than the standard Python json library.

Developer-friendly experience, with an API that feels familiar to that of BeautifulSoup and Scrapy, but improved with extra features, powerful selector options, auto selector generation, regex tools, and more. There is even an Interactive Shell to turn web scraping from a slow, script-and-run process into a fast, exploratory experience.

Adaptive scraping that automatically relocates elements after website changes, reducing maintenance work while keeping scrapers running smoothly without constant selector rewrites.

Reliable session management with persistent cookies, headers, and authentication support, as well as concurrent and async sessions for complex scraping workflows.

In general, all these custom improvements, tweaks, capabilities, and optimizations make Scrapling far more than just a simple wrapper around popular web scraping tools like curl-cfii, Playwright, Camoufox, etc.

This episode is brought to you by our Gold Partners. Be sure to have a look at the Club Deals page to discover their generous offers available for the TWSC readers.

💰 - 1 TB of web unblocker for free at this link

💰 - 50% Off Residential Proxies

💰 - Use TWSC for 15% OFF | $1.75/GB Residential Bandwidth | ISP Proxies in 15+ Countries

Understanding the Scrapling Core Components

Before v0.2, Scrapling was purely a parsing engine, providing only data parsing methods. Now, it also offers fetcher classes to retrieve pages, making it a one-stop solution for all web scraping needs.

Thus, here’s how it works:

Retrieve the target pages using one of the available fetcher classes.

Extract data from the pages using the various data parsing classes.

Afterward, you can return the parsed data using custom data export logic in Python.

To help you understand how the library works, I’ll present its main components, explaining what each one is, what it does, why it’s useful, and the underlying technologies it relies on.

Page Fetching

In Scrapling, fetchers are classes that perform HTTP requests or fetch web pages in a controlled browser instance. They all return a Response object, which works like the Selector class (you’ll learn about shortly) but includes additional features and arguments.

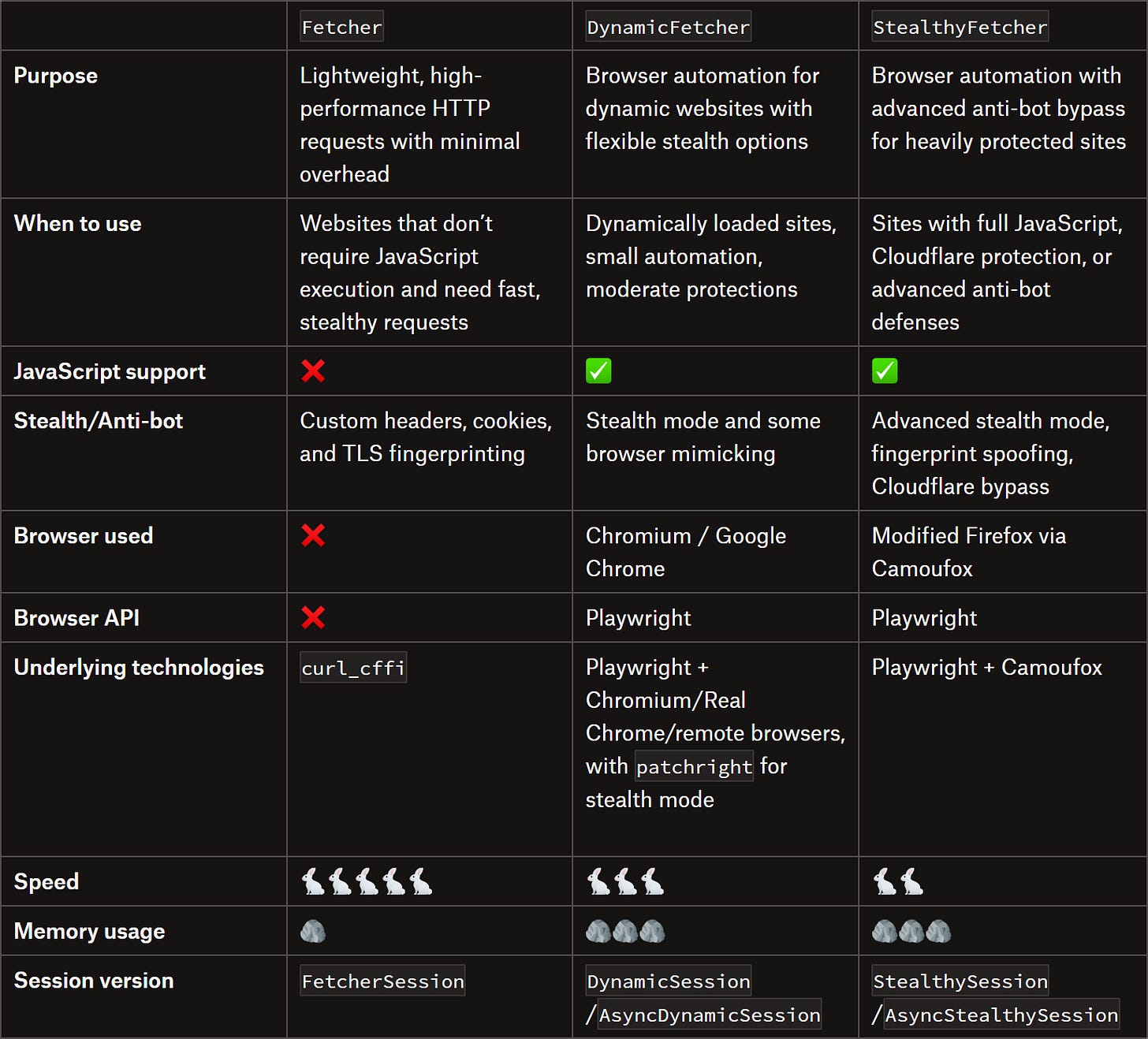

Below are the three main Scrapling fetchers:

Note on sessions

All fetchers have equivalent session classes to keep the session running. For static requests, that’s useful when making multiple requests with the same configuration. The main benefits include:

Up to 10x faster than creating a new session for each request.

Automatic handling of cookies across requests.

Lower memory and CPU usage for multiple requests.

Possibility to manage all request settings in a single place.

For dynamic requests, session classes keep the browser open for multiple requests with the same configuration. This time, the advantages are:

Faster subsequent requests by reusing the same browser instance.

Automatic handling of cookies and session state.

Consistent browser fingerprint across requests.

Fewer resources than launching a new browser each time.

Note on fetchers from D4Vinci

These are some notes on fetchers from the library’s author (thanks for the support in writing this article 😉):

The StealthyFetcher relies on a modified version of Camoufox, which only utilizes the Camoufox browser, but not through its Python library. It only utilizes Camoufox’s Python library for installation and setting the browser launch, but the rest is handled by Scrapling, which also introduces additional capabilities. All these changes aim to make the experience more stable than using the Camoufox library directly, while reducing memory usage and improving robustness.

The DynamicFetcher’s stealth mode relies on patchright, but with numerous improvements and optimizations. These enable it to yield better results than using patchright alone, especially in some instances. More specifically, this stealth mode injects real browser fingerprints, deletes some Playwright fingerprints, and makes all requests appear as if they originate from a Google search of that website (which is a trick used by all fetchers), among other actions.

One of the aspects that makes session classes for StealthyFetcher and DynamicFetcher better and more stable than most libraries is that those two rely on a pool of browser tabs. You define the maximum number of tabs/pages in the pool, and the library rotates visits across them. This makes it possible to send asynchronous requests simultaneously through a single browser with multiple controlled tabs. Learn more in the official docs.

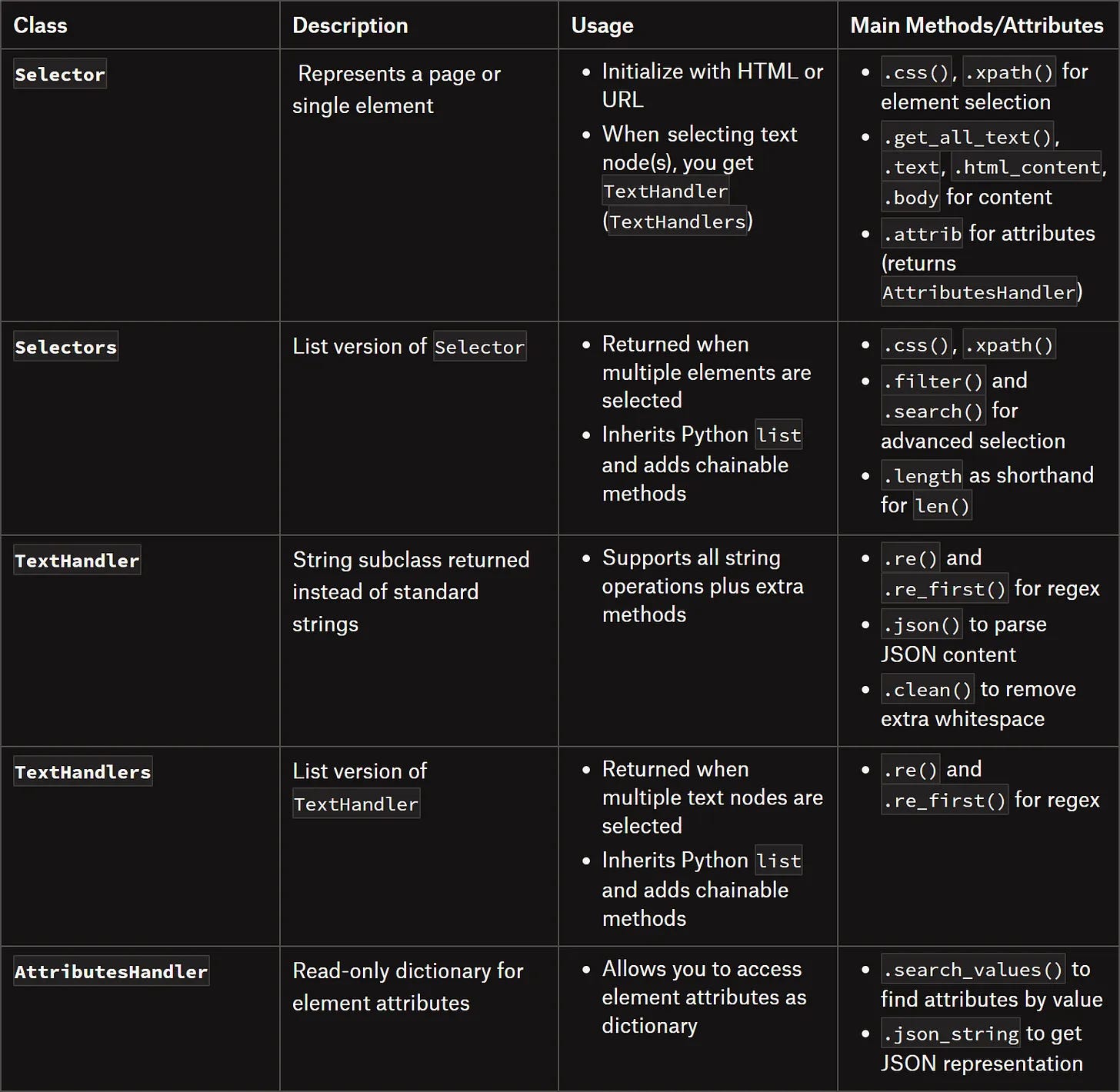

Data Parsing

In Scrapling, there are five primary ways to locate elements:

Using CSS3 selectors

Using XPath selectors

Finding elements based on filters or conditions

Finding elements containing specific text

Finding elements matching a specific regular expression (regex)

Specifically, the main Scrapling classes for data parsing are:

Before continuing with the article, I wanted to let you know that I've started my community in Circle. It’s a place where we can share our experiences and knowledge, and it’s included in your subscription. Enter the TWSC community at this link.

Scrapling in Action: Main Examples

In this section, I’ll show you how to install Scrapling and use it in real-world scraping scenarios through practical Python examples.

Installation and Setup

Note: Starting with v0.3.2, installing the scrapling PyPI package only gives you the parser engine and its dependencies. It doesn’t include fetchers, MCP, or CLI dependencies.

If you plan to use any fetchers, install Scrapling with:

pip install "scrapling[fetchers]"Then, install the fetchers’ extra dependencies (the browsers, any system dependencies, and fingerprint models) with:

scrapling installThe output of that last command should be:

Installing Playwright browsers...

Installing Playwright dependencies...

Installing Camoufox browser and databases...Or:

The dependencies are already installedStatic Site

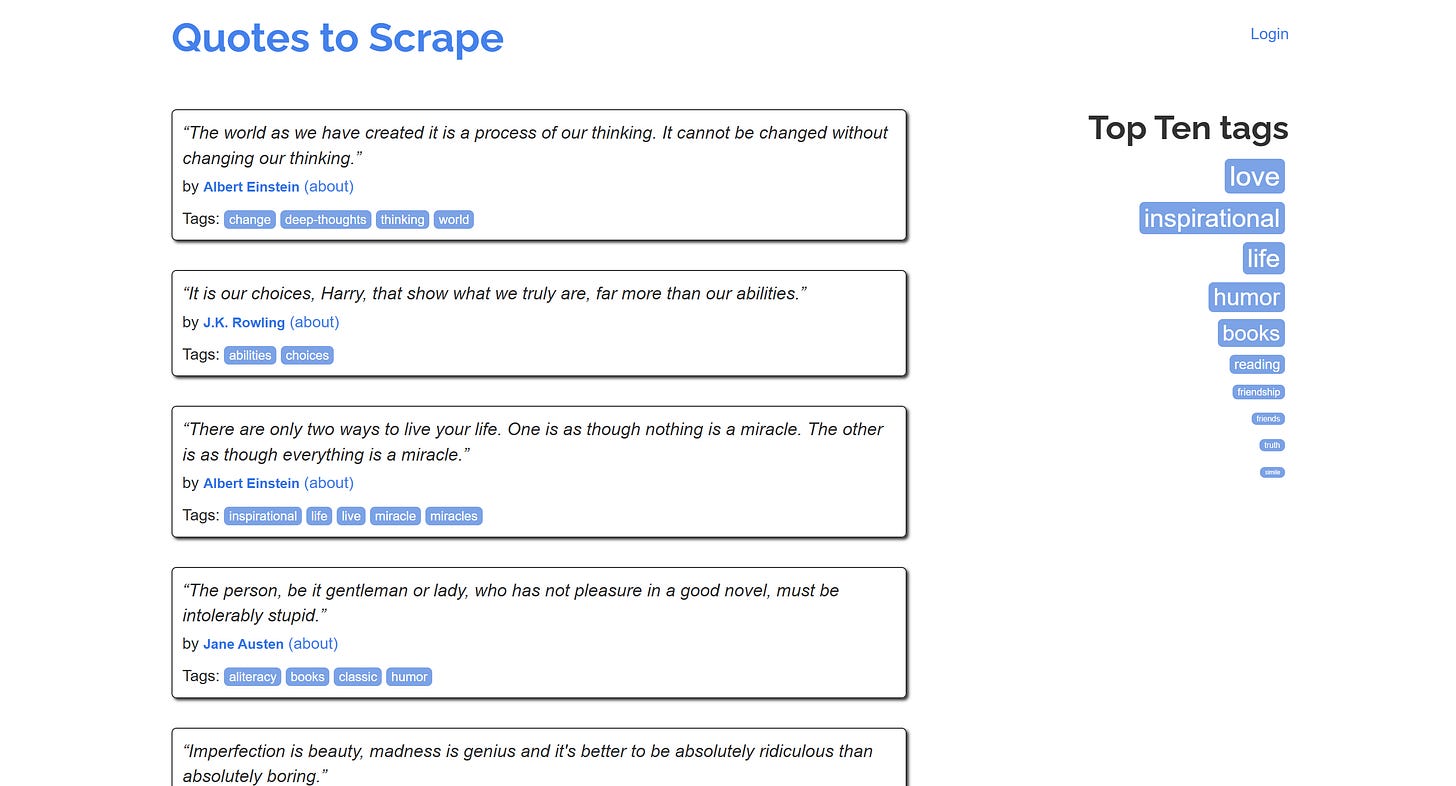

Suppose you want to scrape the classic “Quotes to Scrape” page:

Here’s how you can do it in Scrapling using Fetcher:

from scrapling.fetchers import Fetcher

# Target URL of a static page

url = "https://quotes.toscrape.com/"

# Fetch the page

page = Fetcher.get(url)

# Where to store the scraped data

quotes = []

# Select all quote HTML elements

quote_elements = page.css(".quote")

# Iterate over each quote element and apply the scraping logic

for quote_element in quote_elements:

text = quote_element.css_first(".text::text")

author = quote_element.css_first(".author::text")

tags = [tag.text for tag in quote_element.css(".tags .tag")]

# Keep track of the extracted data

quote = {

"text": text,

"author": author,

"tags": tags

}

quotes.append(quote)

# For debugging

print(quote)

# Data export logic...Pro tip: Using css_first() and xpath_first() is ~10% faster than using css() and xpath() when you’re interested in only the first element. Also, those methods use fewer resources.

Notice how you can access text nodes directly with ::text (just like in Scrapy). Similarly, you can access them via the .text attribute, as shown when scraping the tags.

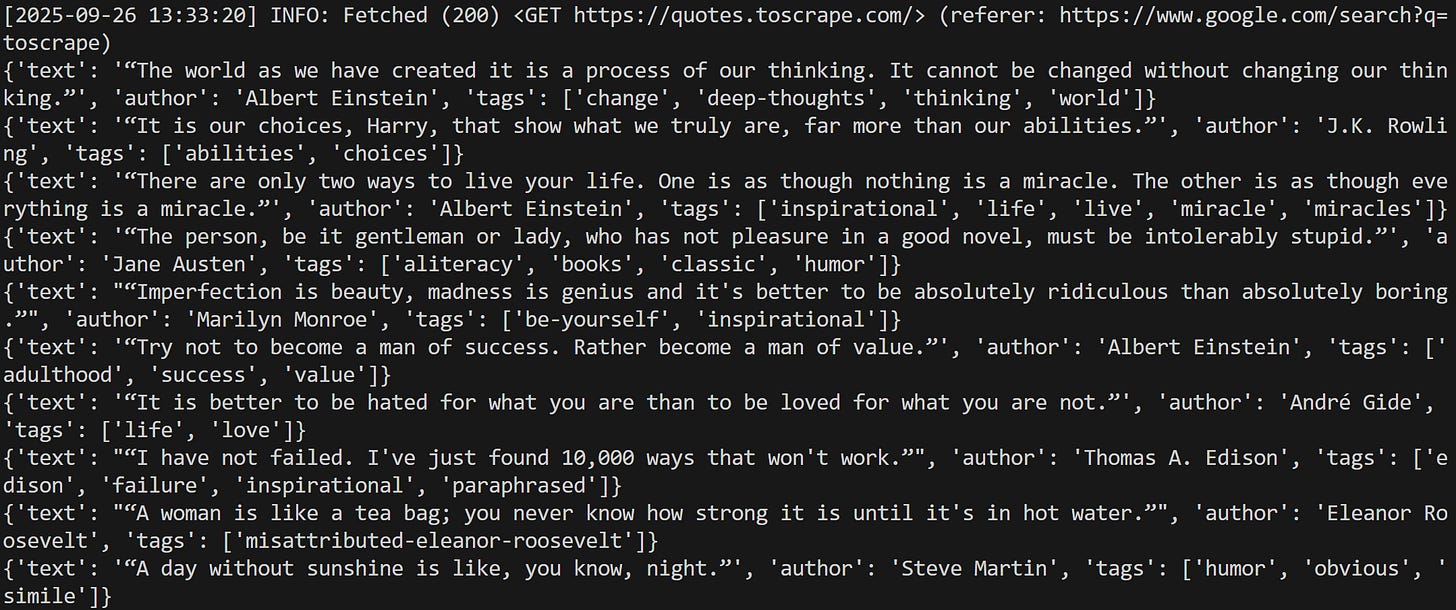

Run the script, and you’ll get:

Great! All quotes have been successfully scraped.

Dynamic Site

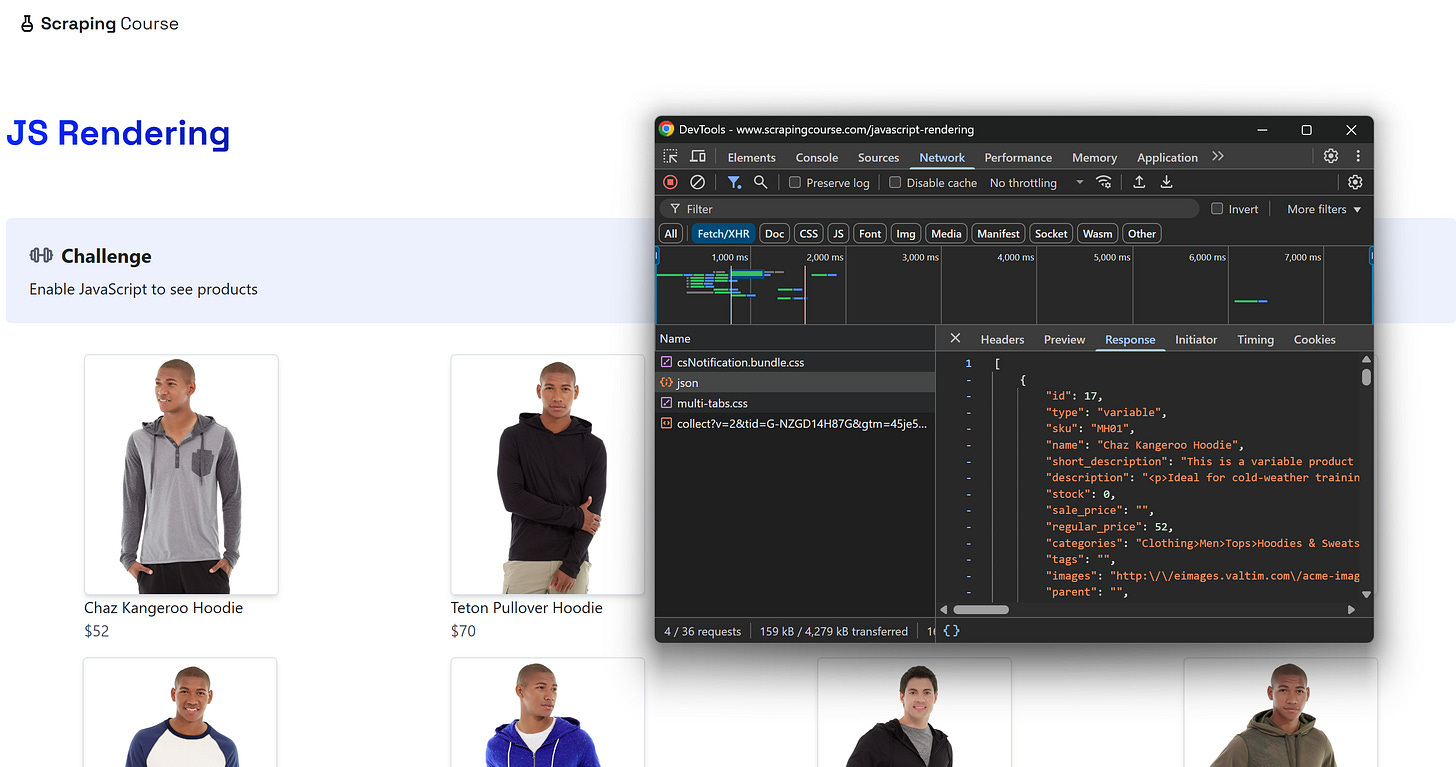

Consider a scenario where you want to scrape an e-commerce-like page that retrieves product data via AJAX, like the “JavaScript Rendering” page from ScrapingCourse:

The page comes with a pre-defined empty structure. The product data is then fetched via an API call in the browser and then inserted into the DOM dynamically using JavaScript. In simple terms, this means you need JavaScript execution to scrape the data, and you must wait for the DOM to be fully populated.

You can handle that easily using Scrapling’s DynamicFetcher:

from scrapling.fetchers import DynamicFetcher

# Target URL of a dynamic page

url = "https://www.scrapingcourse.com/javascript-rendering"

# Fetch the page and wait for the products to load

page = DynamicFetcher.fetch(

url,

wait_selector=".product-link:not([href=''])", # Wait for product nodes to be populated

headless=True # Run in headless mode

)

# Where to store the scraped data

products = []

# Select all product HTML elements

product_elements = page.css(".product-item")

# Iterate over each product element and apply the scraping logic

for product_element in product_elements:

name = product_element.css_first(".product-name::text")

price = product_element.css_first(".product-price::text")

link = product_element.css_first(".product-link::attr(href)")

img = product_element.css_first(".product-image::attr(src)")

# Keep track of the extracted data

product = {

"name": name,

"price": price,

"url": link,

"image": img

}

products.append(product)

# For debugging

print(product)

# Data export logic...Notice how you can access attributes using the Scrapy-like syntax ::attr(href). Alternatively, you can get the same data with the .attrib field:

link = product_element.css_first(".product-link").attrib["href"]Or more concisely, you can access the attributes directly like this:

product_element.css_first(".product-link")["href"]All three approaches are valid. Use whichever feels more convenient for you!

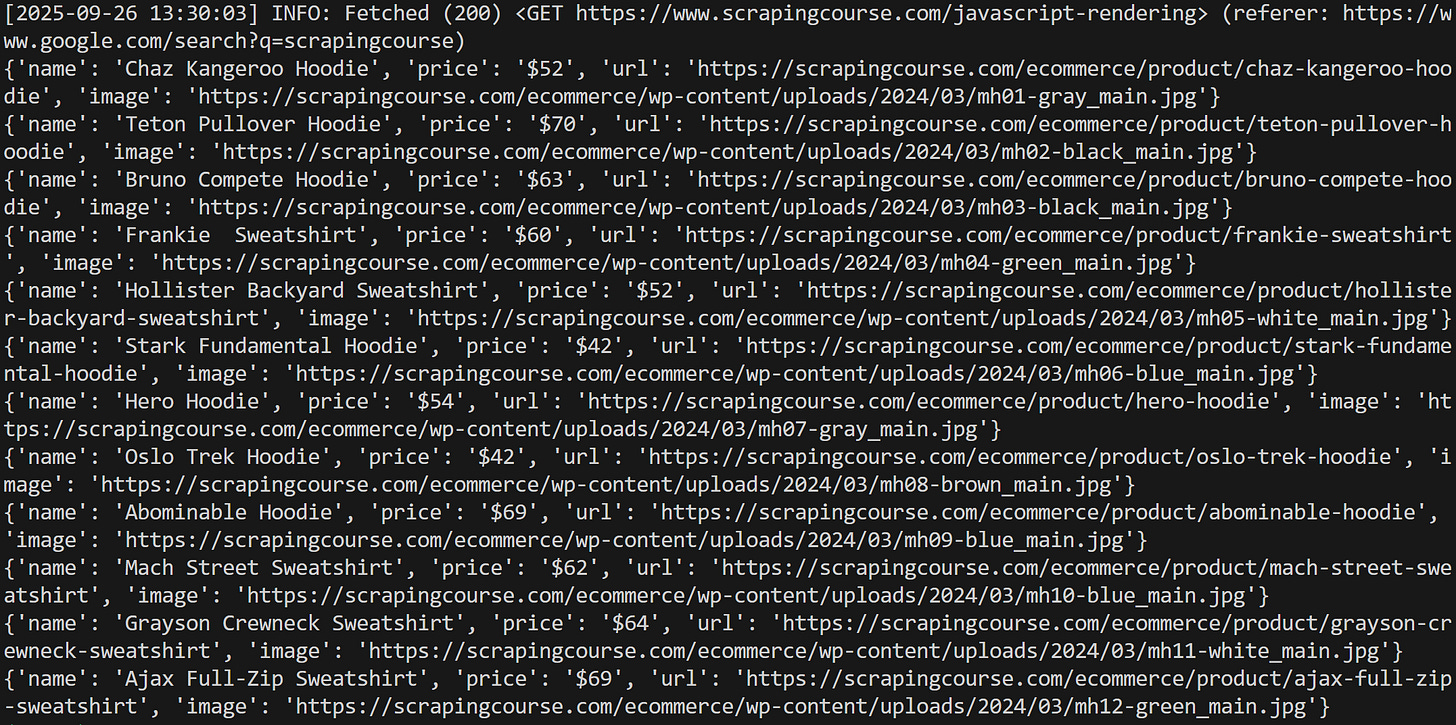

The result will be:

Notice how the script was able to scrape all product data. Well done!

Cloudflare-Protected Site

Focus on a site protected by Cloudflare, such as the “Cloudflare Challenge” page from ScrapingCourse:

This page follows a standard Cloudflare human verification pattern, displaying a Cloudflare Turnstile if it suspects you’re a bot. To bypass it, you need to complete a single check. But, as you probably already know, that’s not easy for automated scripts…

Thanks to Camoufox, Scrapling can handle Cloudflare bypass via the StealthyFetcher as follows:

from scrapling.fetchers import StealthyFetcher

# Target URL of a Cloudflare-protected page

url = "https://www.scrapingcourse.com/cloudflare-challenge"

# Fetch the page with Cloudflare bypass

page = StealthyFetcher.fetch(

url,

solve_cloudflare=True, # Solve Cloudflare's Turnstile wait page before proceeding

humanize=True, # Humanize the cursor movement

headless=True # Run in headless mode

)

# Retrieve the text of the challenge info HTML element

challenge_result = page.css_first("#challenge-info").get_all_text(strip=True)

# Verify whether the Cloudflare human verification challenge was passed or not

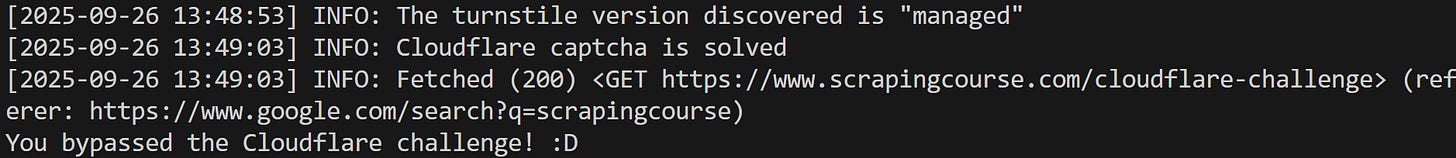

print(challenge_result)The result will be:

Note that the message “You bypassed the Cloudflare challenge! :D” was scraped from the page, showing that the Scrapling bot was actually able to bypass the Cloudflare Turnstile (even in headless mode, which isn’t so easy). Fantastic!

Paginated Site

Now, assume you want to scrape all quotes from the “Quotes to Scrape” website. The site lists quotes across 10 pages, and you want to collect them all. Each pagination page follows this URL pattern:

https://quotes.toscrape.com/page/<PAGE_NUMBER>/To make scraping faster, you can fetch 5 pages at a time asynchronously. Achieve this using FetcherSession as shown below:

import asyncio

from scrapling.fetchers import FetcherSession

async def scrape_page(session, url):

# Asynchronously fetch the page

page = await session.get(url)

# Scraping logic

quotes = []

quote_elements = page.css(".quote")

for quote_element in quote_elements:

text = quote_element.css_first(".text::text")

author = quote_element.css_first(".author::text")

tags = [tag.text for tag in quote_element.css(".tags .tag")]

quote = {

"text": text,

"author": author,

"tags": tags

}

quotes.append(quote)

return quotes

async def scrape_all_pages():

base_url = "https://quotes.toscrape.com/page/{}/"

# Where to store the global scraped data

all_quotes = []

# Starting page

page_num = 1

# Number of pages to fetch concurrently

batch_size = 5

async with FetcherSession(

impersonate="firefox", # Make requests look like as coming from Firefox

retries=3, # Retry attempts in case of errors

) as session:

# Scrape only the first 10 pages

while page_num <= 10:

# Prepare a batch of URLs

urls = [base_url.format(page_num + i) for i in range(batch_size)]

# Fetch pages concurrently

pages_quotes = await asyncio.gather(*[scrape_page(session, url) for url in urls])

# Flatten and add to all_quotes

for quotes in pages_quotes:

all_quotes.extend(quotes)

page_num += batch_size

print(f"Quotes scraped: {len(all_quotes)}")

# Run the async scraper

if __name__ == "__main__":

products = asyncio.run(scrape_all_pages())You might be asking: why use FetcherSession instead of AsyncFetcher? Well, the reason is that FetcherSession works in both synchronous and asynchronous code while allowing multiple requests to reuse the same session. This makes it faster than creating a new session for each request, as it would happen in AsyncFetcher.

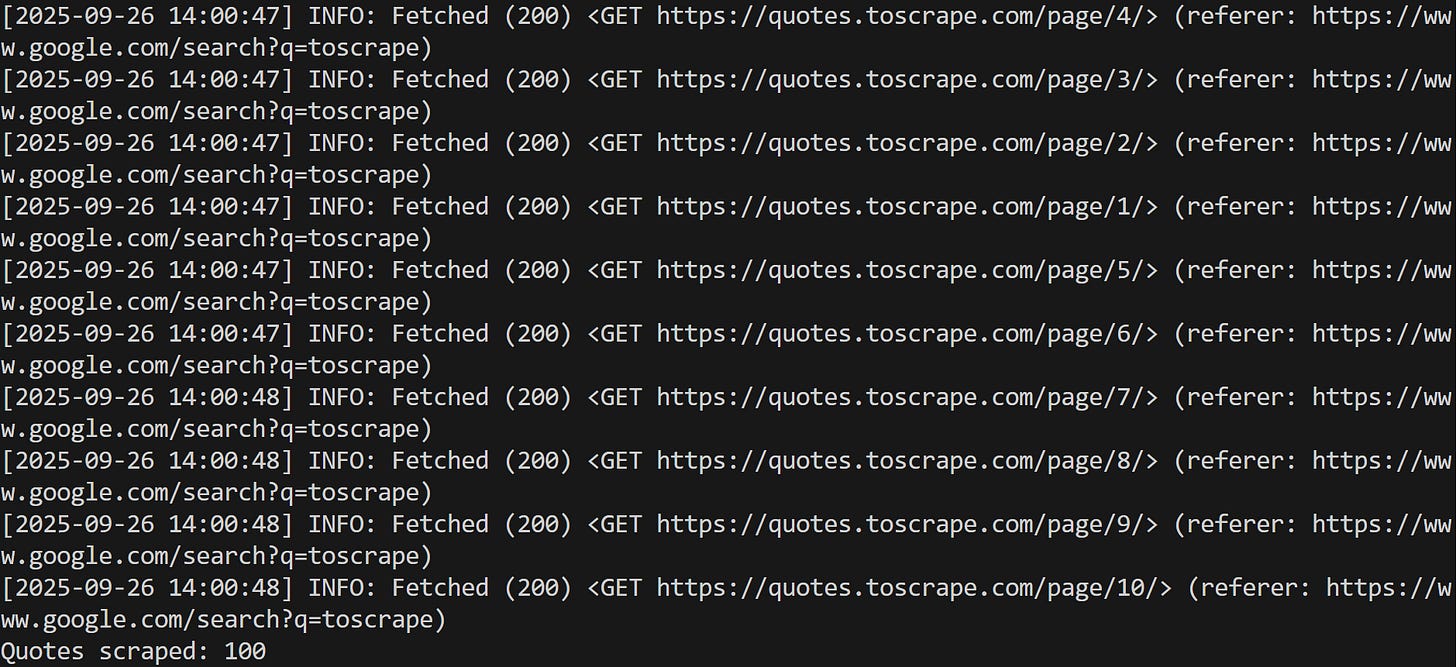

The output will be like this:

Note that the pages are scraped asynchronously (the results will always appear in a different order). The final line shows that all 100 quotes have been successfully scraped. Cool!

Other Cool Scrapling Features

As you now know, Scrapling offers so many features that explaining them all in detail could fill a 10,000-word newsletter post. To keep it concise, remember it also features:

CLI Integration: Scrapling’s command-line interface includes an interactive IPython shell, extract commands to scrape websites without coding, and utility commands for installation and management.

AI MCP Server: Connect Scrapling to AI chatbots or agents via MCP. Scrape websites, extract data, and bypass anti-bot protections directly through the get, bulk_get, fetch, bulk_fetch, stealthy_fetch, bulk_stealthy_fetch MCP tools. (Learn how to use MCP servers in Cursor.)

Conclusion

The goal of this post was to introduce Scrapling and highlight its unique features as a Python web scraping library. As you’ve seen, this solution can do it all, from page fetching to data parsing. It also comes with advanced capabilities like adaptive scraping, similarity search, MCP integration, a dedicated command-line interface, and more.

Remember, this was just an introduction. For further questions or requests, you can reach out to D4Vinci, the author behind this wonderful tool.

I hope you found this article helpful—feel free to share your thoughts and questions in the comments. Until next time!

FAQ

How does adaptive web scraping work in Scrapling?

Adaptive web scraping in Scrapling works by storing unique properties of selected elements (e.g., tags, text, attributes, and parent/sibling info) so that when a website changes, the library can automatically locate elements with the highest similarity score. It involves two phases:

Save Phase, where unique element properties are stored.

Match Phase, where the library retrieves and matches elements on updated pages using CSS/XPath or manual methods.

The goal of this feature is to ensure scrapers keep working automatically, even when website structures change. Discover more in the official docs.

Note: For a complete tutorial, read the “Creating self-healing spiders with Scrapling in Python without AI” guide.

How to integrate proxies in Scrapling?

Scrapling comes with native support for proxy integration. Assuming your proxy URL is:

http://username:password@host:portYou can use it in different fetchers like this:

With Fetcher:

page = Fetcher.get( "https://example.com", proxy="http://username:password@host:port" )With DynamicFetcher:

page = DynamicFetcher.fetch( "https://example.com", proxy="http://username:password@host:port" )With StealthyFetcher:

page = StealthyFetcher.fetch( "https://example.com", proxy="http://username:password@host:port" )

In the CLI, via the --proxy option.

How does HTML element similarity search work in Scrapling?

In Scrapling, HTML element similarity search lets you find elements like a given element using .find_similar(). This method compares DOM depth, tag names, parent/grandparent tags, and element attributes with optional fuzzy matching.

# Find the first element by text

element = page.find_by_text("Tipping the Velvet")

# Find all elements similar to the first one, ignoring the title HTML attribute

similar_elements = element.find_similar(ignore_attributes=["title"])Keep in mind that you can adjust thresholds, ignore attributes, or include text matching.

This mechanism opens the door to the extraction of similar products, table rows, form fields, or reviews efficiently without manually specifying selectors for each element. For full examples of Scrapling’s element similarity features, read the detailed guide in the documentation.

Why use Scrapling MCP Server instead of other available tools?

Scrapling’s MCP Server combines stealth capabilities with the ability to pass a CSS selector in the prompt, allowing you to extract only the elements you need before sending content to the AI. Instead, other MCP tools may be sending the full page content, wasting tokens on irrelevant data. With Scrapling, this targeted extraction makes processing faster and less costly.

I really liked your suggestion.

I have tried Option 2 and used the web unblocker API. They are working and allowing me to scrape data that doesn't require a login, protecting me from hitting a login wall. However, to get complete and accurate data, we need to log in first to see the real and full information.

I am not in favor of using the LinkedIn API from the provider. It is costly and does not yield good results for my requirements. I am more inclined to develop my own LinkedIn solution.

Your valuable input needed. Thank you

Also, where can I find the Discord community link?

I am starting to use it and trying to parse Link*d*n public data, which does not require a login. But after opening it with StealthySession in the browser, it redirects me to the login page; with other proxies, it bypasses that page and gives me the real HTML.