Offline Web Scraping: Download HTML Now, Parse Later

Let’s see why it’s worth keeping a copy of a page’s HTML when scraping it, or even downloading an entire site to scrape it later.

Have you ever been in a situation where you realized you missed some data on a page? Or tested your scraper on a few pages, only to find that when you ran it on the full site, it didn’t retrieve all the data you needed due to inconsistent page structures? Or maybe a site, or some web pages, you were interested in disappeared overnight?

I’ve definitely experienced all of these situations, which is why I’m here to introduce offline web scraping: the art of downloading a site first and extracting data later.

Follow along as I explain everything you need to know about this approach and why it can complement your traditional live web scraping methods!

Before proceeding, let me thank Decodo, the platinum partner of the month. They are currently running a 50% off promo on our residential proxies using the code RESI50.

What Is Offline Web Scraping?

“Offline” web scraping is the process of using a web scraper, website downloader, or crawler to download pages from a website and store them locally or in the cloud. Once saved, you can access those pages and extract data from them, potentially even without needing an active Internet connection (hence the term “offline”).

Simply put, it’s about creating local copies of web pages (similar to using a “website ripper”) so the data they contain can be retrieved later at whatever speed and level of parallelization you want (as you won’t be dealing with issues like IP bans or rate limits).

👍 Pros:

Faster data parsing: Processing data locally is much quicker than repeatedly hitting a live website.

Offline availability: Analyze or re-process data anytime, even without an Internet connection.

Historical preservation: Keep exact snapshots of pages, even if the live site changes or disappears.

👎 Cons:

Large storage requirements: Storing complete HTML documents (especially rendered DOMs) can quickly consume disk space.

Stale data: Once downloaded, pages won’t reflect updates unless you refresh your copies.

Extra setup effort: Downloading, organizing, versioning, and maintaining local site copies adds extra complexity.

When It Actually Makes Sense

Let me present some situations where offline web scraping makes the most sense!

When you need historical data

Sometimes, you’re not interested in live or current data, but rather in historical information (e.g., old news articles, past sports statistics, or previous years’ economic reports). At the end of the day, not all data needs to be fresh (think of how LLMs are trained, as they rely heavily on static, older datasets).

When dealing with historical data, traditional scraping may not be ideal because the content on these pages isn’t going to change. In these situations, you can just download the entire site (or portions of it) first and scrape it at your convenience later, especially if you’re not in a rush.

When a site has a temporary “window of opportunity”

There are situations where anti-bot protections are temporarily relaxed, certain pages are left unprotected, or there’s a misconfiguration or bug that lets you access a site without restrictions (this happened to me when targeting one of the largest sites in Europe).

Building a full scraper from scratch takes time, and by the time you finish, the site’s team may have already identified and fixed the issue. It’s much faster to download the HTML pages while the opportunity exists and focus on data parsing later.

When you want to avoid missing any data

Web pages often contain much more information than what you end up extracting. If you don’t store the full content somewhere, that extra data is lost forever. Later, when you realize that there were other valuable pieces of information you missed, you’ll have to repeat the full scraping process. This not only wastes time but also carries problems, such as the site implementing new anti-scraping measures or having to pay for proxy traffic again.

When page structures are highly variable

Some websites have inconsistent layouts, even across pages of the same type (think of Amazon product pages, which can follow very different structures). That makes your XPath and CSS selectors prone to breaking, working on some pages but failing on others.

As a consequence, you may end up with scraped entries missing fields due to incorrect node selection on certain pages. Storing the HTML of the page allows you to re-parse the data later with improved logic, without having to scrape the site again. That’s why keeping a copy of the original HTML during live web scraping can be considered a best practice.

When a site might disappear “forever”

Websites shut down all the time, oftentimes with no warning. Having your own offline copy makes sure you don’t lose access to valuable data just because the source vanished. Now, let me share a personal work story about this scenario.

A few years ago, a client of mine acquired a domain that included a live site with millions of pages, under the agreement that the original site would soon be shut down. The client was interested in the data on that site, but it was a legacy project (no APIs and a messy database). I was tasked with finding a solution to get that data, and fast!

The solution I came up with was to download the entire site, storing all rendered HTML pages in files on cloud storage. Several years later, I am still occasionally asked to go through those pages to retrieve specific pieces of data. Having that offline copy made it possible to access and retrieve the information reliably, long after the original site disappeared.

This episode is brought to you by our Gold Partners. Be sure to have a look at the Club Deals page to discover their generous offers available for the TWSC readers.

💰 - 1 TB of web unblocker for free at this link

💰 - 50% Off Residential Proxies

💰 - Use TWSC for 15% OFF | $1.75/GB Residential Bandwidth | ISP Proxies in 15+ Countries

Viable Approaches to Offline Web Scraping

See how to implement offline web scraping for both static and dynamic sites.

Static Sites

When dealing with static web pages (pages where all or most of the content is already embedded in the HTML returned by the web server), there are a couple of viable approaches. I’ve personally used both successfully, so which one is “right” really depends on your goals and the needs of your project.

The first approach is to keep track of the full HTML of each unique page while performing web scraping on the fly. After all, the “online” and “offline” approaches to web scraping are not mutually exclusive, and you can start with the online approach, store the HTML somewhere, and then proceed with the offline one.

For example, suppose you’re scraping historical data from a sports site, like past NBA stats. Today you might only be interested in a table of specific stats, but the page could contain much more information. When performing data parsing on the fly, you still need to retrieve the complete HTML first, so it makes sense to save a copy of the page for later use.

The second approach is to use a site downloader to save the entire website to your local machine. Once downloaded, you can access pages directly from your local disk using their filenames rather than the URL (e.g., http://example.com/nba-example-stats.com/nba-stats-2003 becomes nba-stats-2003.html).

Pro alternative: You could start a local web server in the site folder to serve the pages locally (e.g., http://localhost/nba-stats-2003). This allows you to open the index.html file in your browser and explore the site as if it were live. That’s especially useful if the original site has changed since you stored a local copy, helping you familiarize yourself with the exact version of the site you intend to scrape.

Dynamic sites

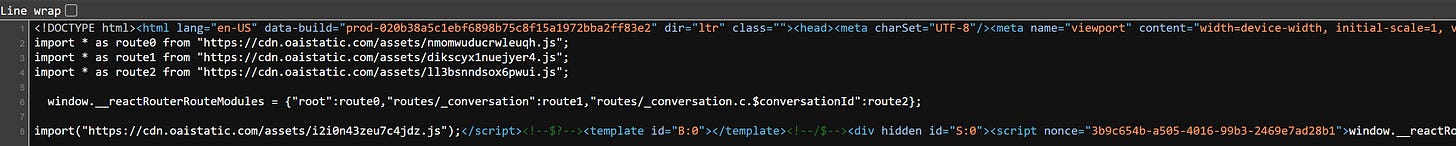

When dealing with dynamic web pages (pages that retrieve content in the browser at render time via AJAX and/or rely on JavaScript for rendering), saving the original HTML document returned by the server usually doesn’t make much sense.

The reason is that the HTML itself often contains very little useful data:

Most of the content comes from third-party resources, such as API calls or JavaScript scripts generated at build time by bundlers like Parcel, Vite, or Webpack.

Even if you download the HTML page and open it locally in your browser, rendering may fail because the API endpoints could have changed, or the JavaScript bundles (which typically change with each deployment) may no longer match.

In these cases, you need to store the rendered version of the DOM rather than the original HTML. Thus, the workflow is:

Connect to the web server.

Retrieve the HTML document.

Render it in a browser automation tool like Playwright, Selenium, or Puppeteer.

(Optionally perform live data parsing and extraction.)

Store the resulting HTML from the rendered DOM (potentially even after simulated user interactions, such as when dealing with infinite scrolling).

Pro Tips and Best Practices for Offline Web Scraping

Based on my experience with offline web scraping, here are some tips and best practices:

Compress the original HTML: HTML is just a text string, and compressing it with algorithms like gzip can reduce storage size by 70–80%, saving space and speeding up transfers.

Store HTML in cloud storage: Whether original or rendered, you can store HTML documents in cloud storage via S3. This allows easy access from multiple machines and helps with backups and sharing.

Store HTML in a database: Store HTML directly in your database using dedicated columns—either as raw text or as compressed binary data. For example, when scraping a page, you can insert it into a scraped_pages table with columns for the URL, date, and HTML content (or, better, a link to the S3 file). Such table also helps track which pages have already been scraped.

Keep metadata for each page: Along with the HTML, consider storing metadata such as timestamp, HTTP status code, and response headers. That makes debugging and incremental scraping easier.

Version your scraped data: If a page changes over time, consider storing multiple versions instead of overwriting the old one. This allows you to analyze changes and maintain a historical record, just like how the Wayback Machine works.

Before continuing with the article, I wanted to let you know that I've started my community in Circle. It’s a place where we can share our experiences and knowledge, and it’s included in your subscription. Enter the TWSC community at this link.

Main Challenges of This Approach to Web Scraping

Based on my experience, offline web scraping comes with two major challenges, especially in large-scale projects:

High HTML storage costs: Saving a full copy of every scraped HTML page can quickly eat up disk space. In projects collecting millions of pages, storage costs (especially in the cloud) can’t be ignored. To manage this, I recommend using strategies like data compression, local storage, and a smart data management system. Plus, make sure to store only the information you really need (e.g., you may not need images), and avoid duplication.

Scraper versioning: The scraper you use today on a site may not work correctly against the same site as it appeared a year ago. The consequence is that you might need to maintain two sets of scrapers: one for older, stored versions of web pages, and another for the current live site. You may also require a database structure to handle versioned data.

How to Download a Website for Offline Web Scraping

There are several ways to download the pages you need for offline web scraping. For small sites, especially those not protected by strict WAFs like Cloudflare, it can be better to download the entire site using a website downloader—without wasting time figuring out which pages to save and which ones to ignore.

A simpler approach is to identify the site’s sitemap (either by checking robots.txt or visiting something like http://your-target-site.com/sitemap.xml) and retrieve only the URLs you’re interested in (e.g., all URLs containing /blog/). You can then download those pages selectively.

In more complex scenarios, you might prefer to use (or even build) a link-discovery crawler. Such a crawler starts from a given page, follows links to find new URLs, and downloads the pages as it discovers them. You can implement that using standard search algorithms, such as Depth-First Search (DFS) or Breadth-First Search (BFS), while filtering for pages with a specific structure or containing certain keywords (e.g., /products/).

Open-Source Tools for Offline Web Scraping

Open-source tools you can use for website downloading (and therefore for offline scraping) include:

Note 1: You can also build your own script (using the approaches mentioned earlier), applying custom logic or tools like Scrapy.

Note 2: If you’re looking for website downloading solutions, search for terms like “website rippers,” “website suckers,” “website downloaders,” or “website copiers,” as these are the most commonly used terms to describe these types of tools.

Offline Web Scraping vs Traditional Web Scraping: Summary Table

Conclusion

The goal of this post was to explain the offline approach to web scraping. As you’ve learned, keeping a copy of the original HTML—or approaching a site with the idea of downloading pages first—can be beneficial for many reasons and in a variety of scenarios.

The main advantage is that you’ll have the raw source data stored locally or in the cloud, giving you full control over how to process it without worrying about site changes or anti-scraping measures.

I hope you found this article helpful. Feel free to share your thoughts, questions, or experiences in the comments—until next time!