Using Python’s Async Features for High-performance Scraping

From theory to practice: why async is better for scraping at scale

If you’ve been scraping for a while, I’m sure that, at the very beginning of your career, your scraping scripts executed HTTP requests synchronously. Also, I’m pretty sure you never heard of the possibility of scraping asynchronously until you tried to scale your scripts. Sounds familiar?! I bet it does!

In this article, I’ll point out the differences between synchronous and asynchronous scraping, and why asynchronicity is the right choice if you want to scrape at scale.

Ready? Let’s dive into it!

Before proceeding, let me thank NetNut, the platinum partner of the month. They have prepared a juicy offer for you: up to 1 TB of web unblocker for free.

The Inefficiency of Sequential HTTP Requests

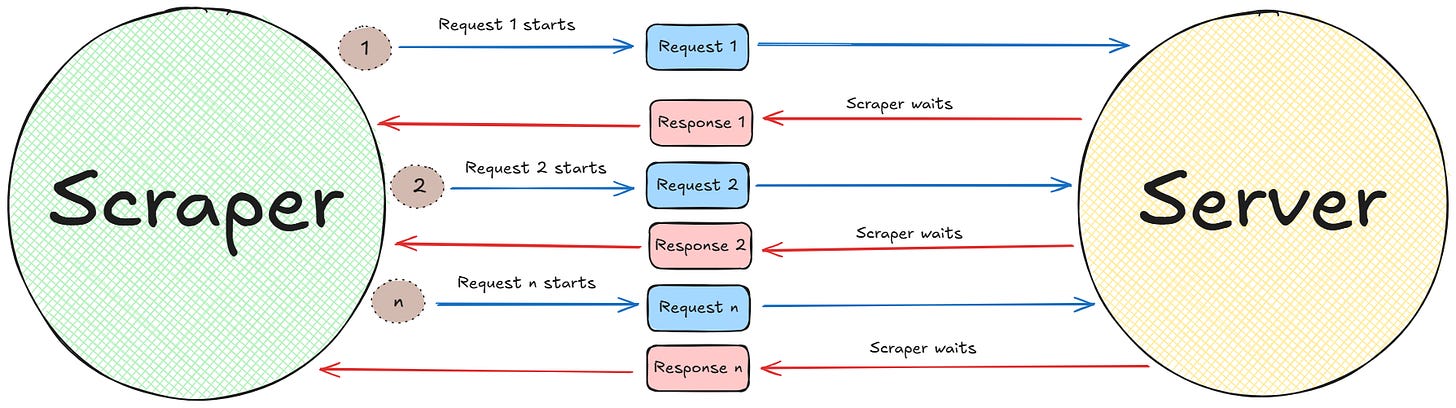

The easiest way to get started with web scraping is by sending synchronous requests to a web server. In synchronous scraping, whenever your program sends a request, it waits until that request has completed. In other words, your program executes one request at a time until the server responds. So each request is sent and processed sequentially.

Below is a schema that shows how this process works:

Let’s be honest for a moment: Is not that synchronous scraping is bad at all. But processing one request at a time is a performance bottleneck for large-scale scraping. This is because of two main reasons:

Executing “n” requests one after another takes a lot of time if “n” is large.

If one of the requests fails, you must restart the scraping process from the beginning. Imagine the sensation of seeing your scraper fail the 29th request while it had to complete 80. Not your best working day, I suppose.

On the side of the technicalities, a program that scrapes data from the web is I/O-bound (Input/Output bound). In computer science, a program is I/O-bound when the rate at which it can complete its work is limited by the speed of its I/O subsystems, rather than the speed of its processor.

In the case of a web scraper, the primary I/O operation is waiting for data to travel over the network. This wait time can range from milliseconds to several seconds per request. So, if it processes several requests sequentially (aka, synchronously), the “n-th” request can take several minutes before it has completed. Often, such a great time is simply not acceptable.

Let’s consider a Python snippet to see where the bottleneck can actually be in a simple case:

import requests

import time

def fetch_url(url):

"""Sends a GET request and waits for the response."""

try:

# EXECUTION BLOCKS HERE: The program pauses until the server responds

response = requests.get(url, timeout=10)

print(f"Completed: {url}, Status: {response.status_code}")

except requests.RequestException as e:

print(f"Failed: {url}, Error: {e}")

# A list of 15 URLs to scrape

urls = [

"<http://example.com>",

"<http://example.org>",

"<http://example.net>"

] * 5

print("Starting synchronous scrape...")

start_time = time.time()

# Loop throguh all the URLs in the list

for url in urls:

fetch_url(url)

duration = time.time() - start_time

print(f"\\nFinished. Total time: {duration:.2f} seconds.")

In the above snippet, the execution flow is linear:

The for loop initiates a request for the first URL.

The program waits for the response to arrive (with the method requests.get().

Once the response arrives, the program moves to the second URL, initiates a new request, and waits again. This cycle repeats for all 15 URLs.

In synchronous scraping, the total execution time is roughly the sum of the network latency for every single request. If an average request takes 500ms, scraping just 1,000 URLs would take a minimum of 500 seconds: over 8 minutes. During this time, the scraper’s process is doing nothing but waiting.

As expected, this model is fundamentally inefficient if you want to scale to thousands or millions of pages.

Sending so many requests in a short period of time, from the same IP address, could lead to a block for your scraper. For this reason, we’re using a proxy provider like our partner Ping Proxies, that’s sharing with TWSC readers this offer.

💰 - Use TWSC for 15% OFF | $1.75/GB Residential Bandwidth | ISP Proxies in 15+ Countries

Why Asynchronous is the Solution for Scraping at Scale

As with any technical solution, it is not that synchronous scraping is bad at all. If you are working on “little” projects, synchronous scraping is just fine. The problems start to manifest themselves when you want to scrape at scale. In this case, the right solution is to implement an asynchronous strategy.

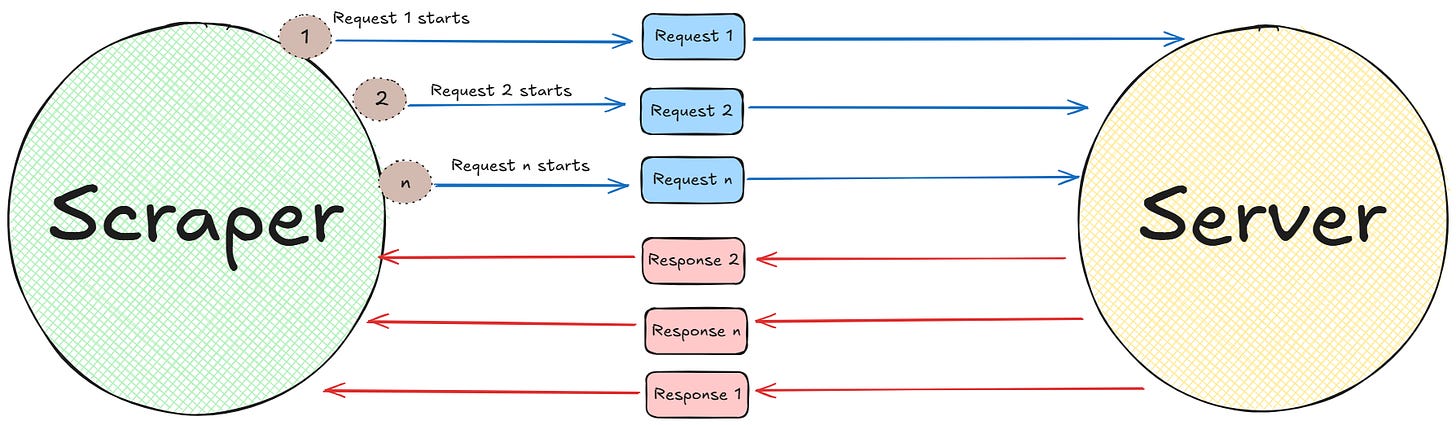

The asynchronous approach is designed to optimize performance for I/O-bound workloads by enabling concurrent execution of operations within a single thread. Instead of executing tasks sequentially, an asynchronous program initiates multiple operations and manages them simultaneously. In other words, an asynchronous scraper starts several requests at the same time and processes them as they complete, without the need to wait.

Below is a schema that shows how async requests work at a high level:

As the image shows, in the case of async requests, if response 1 takes more time than response n, the program works just fine. This is the actual power of async scraping: no need to wait sequentially. Everything ends when it needs to end, without creating bottlenecks.

Below is a list of the reasons why this approach is better suitable for large-scale scraping:

Decrease in total execution time: In synchronous scraping, the total execution time is the sum of the time it takes to each request to arrive to the server and return back to the scraper (response time). Asynchronous execution changes this equation. By initiating several requests concurrently and processing them as they complete, the program overlaps the I/O wait times. So, in this case, the total execution time is no longer the sum of all execution times. Instead, the number of concurrent requests and the duration of the longest requests in each batch dictates the total execution time, which is way shorter.

Maximized resource efficiency: In the synchronous model, the CPU is idle for the vast majority of the program’s lifecycle, as it waits for network I/O. This is a waste of computational resources. In particular, if you apply this model to scrapers running on cloud infrastructure, you are paying for CPU time that you don’t actually use. An asynchronous scraper, on the other hand, maximizes CPU utilization. In fact, while one task is waiting for the network, the CPU is can be repurposed to advance another task, whether that means initiating a new request or parsing the HTML from a completed one.

Enabling real-time data acquisition: For many scraping applications, the value of data decays rapidly. In such cases, a synchronous scraper that takes hours to complete a cycle provides data that is already old by the time the scraper finishes its job. Think, for example, at applications like stock price scraping or e-commerce prices scraping during discount seasons. These are applications where the nature of the asynchronous approach allows for near real-time data acquisition, allowing you to take decisions fast.

The Asynchronous Toolbox in Python

If you’ve been developing in Python for a while, you know how versatile this programming language is. Among all the possibilities, it provides you with several ones for creating asynchronous scrapers. This section discusses them all.

Python’s Async Core Engine: asyncio

The asyncio framework is the core of modern asynchronous Python scrapers. It is not a scraping library itself. Rather, it is a low-level framework that provides the infrastructure for running concurrent requests. As part of the Python standard library since version 3.4, it is the universally accepted engine for asynchronous operations.

Its primary components include:

The event loop: This is the central coordinator of the operations. It manages, distributes, and monitors the execution of all asynchronous tasks. When a task declares it is waiting for I/O, the event loop suspends it and runs another task that is ready to go.

Coroutines: These are functions (defined with async def) that can be paused and resumed by the event loop. They form the basic unit of an asyncio application.

Tasks: These are wrappers for coroutines that schedule them for execution on the event loop. For example, the asyncio.gather() is a common utility for running multiple tasks concurrently.

Python’s Asynchronous HTTP Client: aiohttp

aiohttp is a widely used library that serves as the primary asynchronous replacement for the library requests. It provides a comprehensive toolset for making HTTP requests within an asyncio application.

It is an excellent choice when you need fine-grained control over the request-response cycle and are building a custom solution on top of asyncio. Also, it is a library, not a framework. This means that it provides the tools for I/O, but leaves the application’s structure and data processing logic entirely up to the developer.

Its key features include:

Client-side HTTP support: Its core feature is the aiohttp.ClientSession. This class manages a connection pool, which is critical for performance. Reusing connections avoids the overhead of establishing a new TCP connection and performing a TLS handshake for every single request.

Awaitable methods: The library provides all network-bound operations, such as session.get() or response.text(), as coroutines that must be called with await. This allows them to yield control to the event loop while waiting for the network, enabling request concurrency.

Python’s All-in-One Framework: Scrapy

Scrapy is a powerful web scraping and crawling framework. The distinction between a library and a framework is very important: A library (like aiohttp ) gives you tools; A framework (like Scrapy) gives you an entire architecture. Scrapy is designed from the ground up for building robust, production-grade spiders that can handle complex, large-scale crawling projects. Also, while it has been around for over a decade, Scrapy still continues to be highly relevant in data extraction and web scraping.

Among all the features it provides, the ones tight to asynchronicity are:

Event-driven core: Scrapy is built on top of Twisted, a mature, event-driven networking engine. This architecture allows Scrapy to handle thousands of requests concurrently with very low resource overhead.

asyncio integration: While its core is Twisted, starting from version 2.0, Scrapy partially supports the integration with asyncio. This integration is possible thanks to the scrapy-asyncioreactor, which lets you use asyncio and asyncio-powered libraries in any coroutine.

Declarative concurrency: In Scrapy, you don’t typically manage an event loop directly. Instead, you write a Spider class and yield scrapy.Request objects from your parsing methods. The Scrapy Engine, acting as the central controller, asynchronously schedules the requests, sends them via its Downloader, and routes the responses back to the right callback method. This model abstracts the complexity of manually managing concurrency, simplifying the work on the developers’ side.

In Scrapy, you can also easily integrate the proxies from our partner Rayobyte.

💰 - Rayobyte is offering an exclusive 55% discount with the code WSC55 in all of their static datacenter & ISP proxies, only to web scraping club visitors.

You can also claim a 30% discount on residential proxies by emailing sales@rayobyte.com.

Async Scraping: Step-by-step Tutorial

Let’s set up an example to show the difference in execution time when you scrape the same data with sync and async programs.

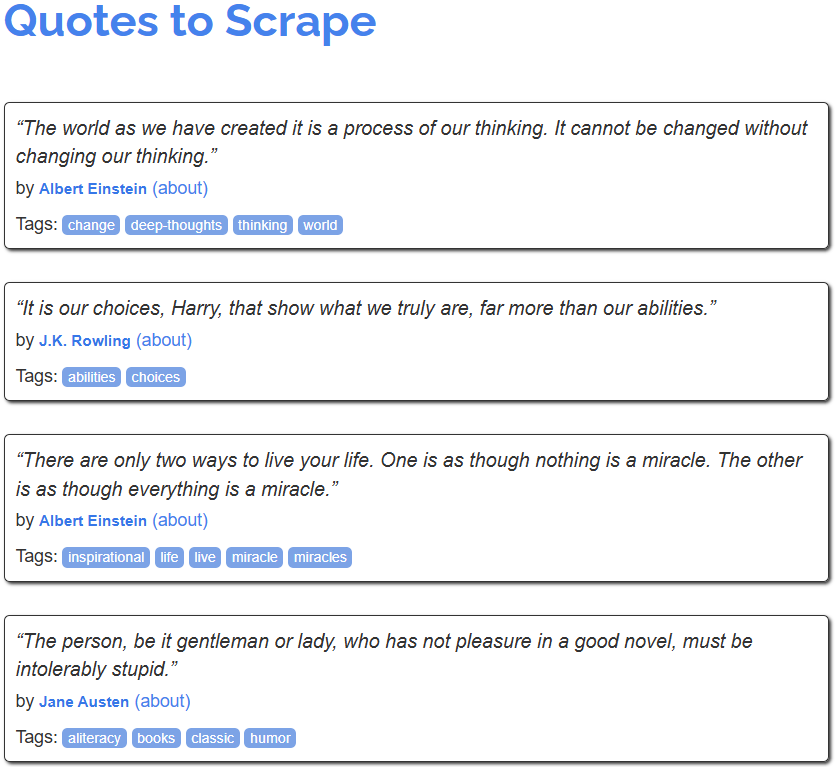

In this tutorial section, you will scrape the first ten pages from quotes.toscrape.com, extracting all the quotes’ text and author:

Follow me through the next subsections to learn how to do so.

Requirements and Prerequisites

To reproduce the following tutorials, you need at least Python 3.10.1 installed on your machine.

Name the main folder of your project sync-async-scraping/. By the end of this section, the folder will have the following structure:

sync-async-scraping/

├── sync-scraper.py

├── async-scraper.py

└── venv/Where:

sync-scraper.py is the Python file that will scrape the target website synchronously.

async-scraper.py is the Python file that will scrape the target website asynchronously.

venv/ contains the virtual environment.

In the activated virtual environment, install the needed libraries:

pip install requests aiohttp beautifulsoup4Perfect! Everything is set up to proceed with the scraping tutorials.

Scraping Tutorial #1: Synchronous Scraping

Let’s begin with the synchronous approach. In this case, the script will request one page, wait for it to download, parse it, and only then move on to the next page, until the 10th one.

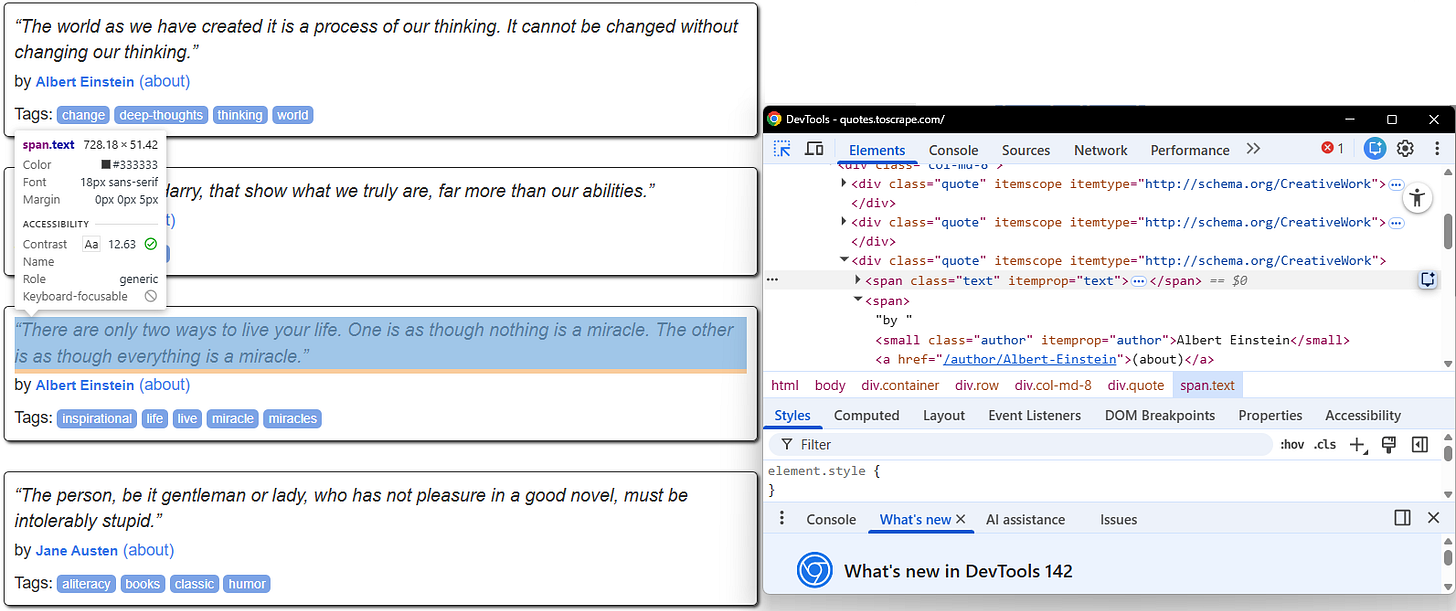

The image below shows the selectors that the scraper will intercept:

To scrape the first ten pages synchronously, you can write the following Python script in the sync-scraper.py file:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import time

def get_quotes_from_html(html):

"""Extracts all quotes from a page’s HTML content using CSS selectors."""

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, "html.parser")

quotes = []

# Return a list of all matching elements

for quote in soup.select("div.quote"):

# Find the first matching child element

text = quote.select_one("span.text").get_text(strip=True)

author = quote.select_one("small.author").get_text(strip=True)

quotes.append((text, author))

return quotes

def main():

"""Main function to scrape quotes synchronously."""

base_url = "<http://quotes.toscrape.com/page/{}/>"

all_quotes = []

print("Starting synchronous scrape...")

for page_num in range(1, 11): # Scrape first 10 pages

url = base_url.format(page_num)

try:

response = requests.get(url, timeout=10)

response.raise_for_status()

print(f"Fetched {url}")

quotes = get_quotes_from_html(response.text)

all_quotes.extend(quotes)

except requests.RequestException as e:

print(f"Could not fetch {url}: {e}")

print(f"\\nTotal quotes found: {len(all_quotes)}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

start_time = time.time()

main()

duration = time.time() - start_time

print(f"Synchronous scraper took {duration:.2f} seconds.")

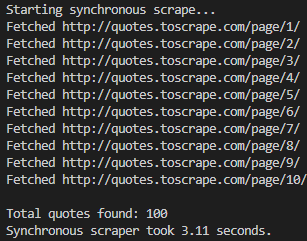

After running the sync-scraper.py, you will obtain a result like the following:

As the image shows, the scraper fetched the content of the first 10 pages in ascending order (from page 1 to page 10). The overall process took 3.11 seconds.

The question now is: for only 10 pages, will the async do better, on the side of overall execution time? And if so, by how much? Let’s see this in the next paragraph!

Scraping Tutorial #2: Asynchronous Scraping

In this section, you will only refactor the scraping logic to be asynchronous. The target page and everything else remain the same. In this case, the scraper will initiate all 10 page requests concurrently and process them as they complete.

To do so, use the following code in the async-scraper.py file:

import asyncio

import aiohttp

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import time

def get_quotes_from_html(html):

"""Extracts all quotes from a page’s HTML content using CSS selectors."""

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, "html.parser")

quotes = []

# Return a list of all matching elements

for quote in soup.select("div.quote"):

# Find the first matching child element

text = quote.select_one("span.text").get_text(strip=True)

author = quote.select_one("small.author").get_text(strip=True)

quotes.append((text, author))

return quotes

async def fetch_page(session, url):

"""Coroutine to fetch a single page’s HTML content."""

try:

async with session.get(url, timeout=10) as response:

response.raise_for_status()

print(f"Fetched {url}")

return await response.text()

except Exception as e:

print(f"Could not fetch {url}: {e}")

return None

async def main():

"""Main coroutine to orchestrate the asynchronous scraping."""

base_url = "<http://quotes.toscrape.com/page/{}/>"

urls = [base_url.format(page_num) for page_num in range(1, 11)]

all_quotes = []

print("Starting asynchronous scrape...")

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [fetch_page(session, url) for url in urls]

html_pages = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

for html in html_pages:

if html:

quotes = get_quotes_from_html(html)

all_quotes.extend(quotes)

print(f"\\nTotal quotes found: {len(all_quotes)}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

start_time = time.time()

asyncio.run(main())

duration = time.time() - start_time

print(f"Asynchronous scraper took {duration:.2f} seconds.")

As you can see, the get_quotes_from_html() function that extracts the HTML remains the same. What changes is how it is called—asynchronously, in this case.

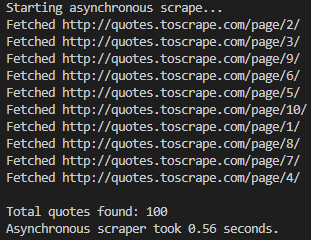

After running the async-scraper.py, you will obtain a result similar to the following:

As you can see from the image above:

The 10 pages are not scraped in ascending order.

The total execution time is only 0.56 seconds.

So, for only ten pages, the async scraper has decreased the execution time from about 3 seconds to half a second. In other words, for only ten pages, the async architecture diminished the total execution time by about six times: a huge time saving!

Conclusion

Like any technical solution, there is no one that is good for every case. You need to choose the right solution for your specific problem. So, as you’ve read along this article, is not that synchronous scraping is bad at all. The point is that asynchronicity is better suitable for large-scale scraping projects.

In fact, as you have learned in the tutorial section, an asynchronous scraper can lower the execution time by three times when scraping just 10 pages. A huge saving of time!

So, let’s discuss in the comments: how are you managing concurrent requests in your Python scrapers?