THE LAB #94: Using cookies and session for cost-effective scraping

Trying to scrape from Leboncoin, Allegro and Idealista without emptying our pockets.

One of the latest issues of the ByteByteGo newsletter was a simple schema about Cookies Vs Sessions, which is also a topic I’ve been studying recently for some scraping projects I’m following, so I decided to share my notes on this with you.

Before proceeding, let me thank Decodo, the platinum partner of the month. They’ve just launched a new promotion for the Advanced Scraping API, and you can now use code SCRAPE30 to get 30% off your first purchase.

One note from me before continuing this article.

This is not very scraping-related, but I wanted to share something with you. Angel, a person in the scraping industry and owner of a company in Bulgaria, is facing tough times due to his past health conditions.

While his health is slowly recovering, and he has started working again, the debt for the medical bills keeps rising.

He started an online fundraising campaign for anyone willing to help him, even with small sums. As a small entrepreneur, this history really hit me since I have known Angel for some time, and it reminds me how important our health is and how quickly things can go wrong.

Thank you!

Cookies and sessions: definitions and differences

Let’s start from the basics: HTTP is a stateless protocol, meaning that each request a client sends to a server is independent and self-contained. The server does not retain any information (state) about previous requests from that same client.

Cookies and sessions are ways to link different requests and can be used together, but the main difference is where the information is stored.

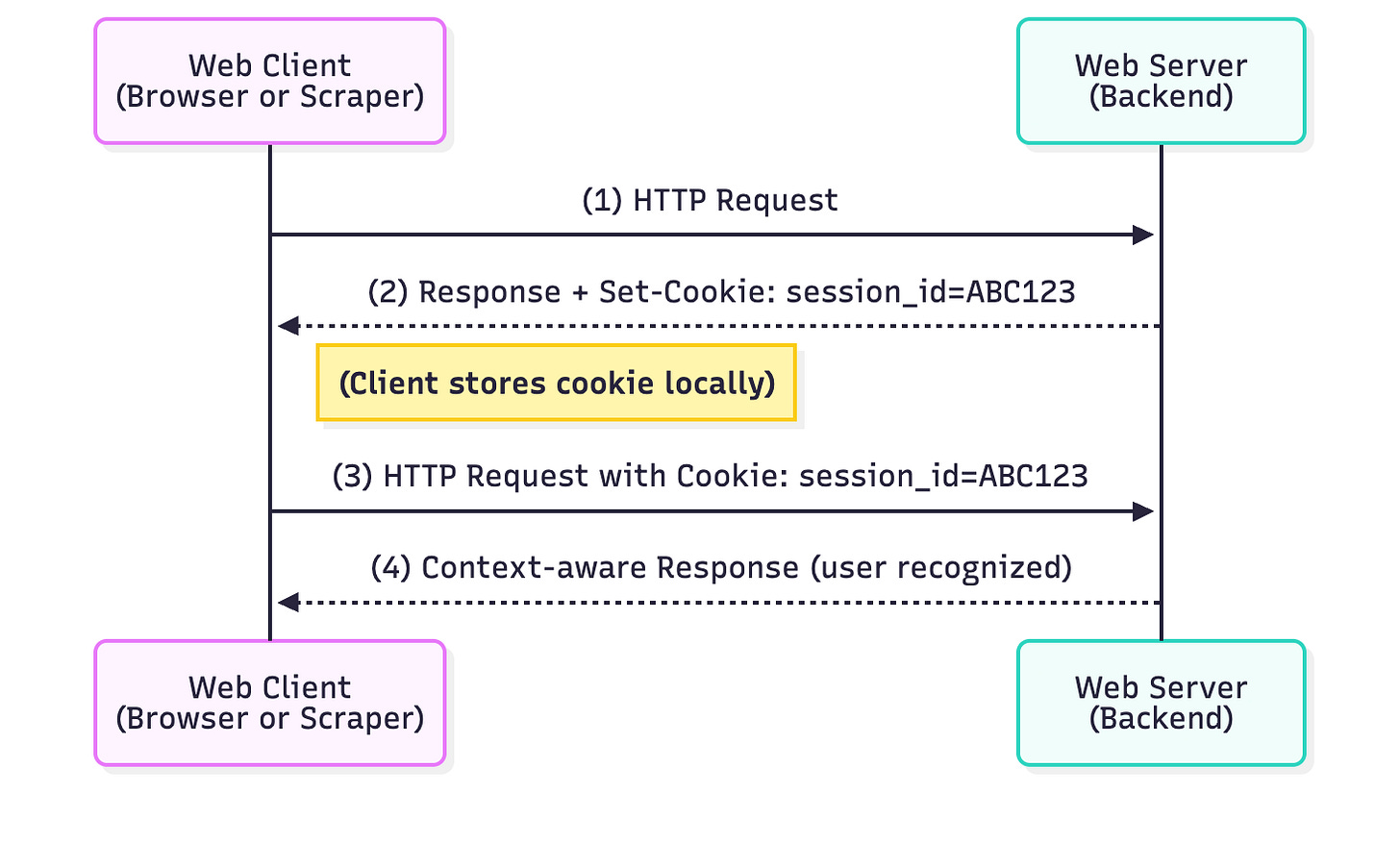

Cookies enable state by telling the client to store a small token. In a typical HTTP exchange, a web client sends a request (1) and receives a response containing a Set-Cookie header from the server (2). The client (browser or script) then stores this cookie and automatically includes it in future requests to the same server (3), allowing the server to recognize the client and maintain context when responding (4). Because HTTP is stateless, cookies provide a key mechanism for maintaining user state across multiple requests. A cookie is essentially a small piece of data (often a name-value pair) stored on the client side (browser or HTTP client). Cookies can serve various purposes – session identifiers, user preferences, tracking info, etc. They have attributes like domain, path, expiration, and flags (HttpOnly, Secure), which govern scope and security.

Sessions rely on a unique session ID to maintain continuity. In web terms, a session represents a continuous interaction between a client and a server, often implemented by linking multiple requests with an identifier. For example, when you log into a website, the server creates a session (server-side record) and issues a session ID – usually via a cookie like sessionid or similar – in the login response. The client then includes this session ID cookie in each subsequent request, allowing the server to retrieve the stored session data (e.g. your authenticated user info, shopping cart contents) and thus remember who you are across pages. In other words, the session is the state stored on the server (or sometimes on the client in a token) and the cookie is the key that the client uses to access that state. Without the cookie containing the session ID, the server would treat every request as new, and you’d lose the continuity of being “logged in” or mid-process in a multi-page form.

This episode is brought to you by our Gold Partners. Be sure to have a look at the Club Deals page to discover their generous offers available for the TWSC readers.

💰 - 55% discount with the code WSC55 for static datacenter & ISP proxies

💰 - Get a 55% off promo on residential proxies by following this link.

🧞 - Reliable APIs for the hard to knock Web Data Extraction: Start the trial here

We can summarize the differences in this way:

Lifetime & Scope: Cookies can persist on the client until they expire (they remain on the user’s device until expiry or deletion), whereas server-side sessions usually expire after a certain inactivity period or when the user logs out, and are cleared on the server. Session cookies (without expiry) last until the browser session ends (browser close), providing short-term state, while persistent cookies can last days or months (for “remember me” logins, etc.).

Storage & Security: Cookies are limited in size (usually around 4KB) and stored in plain text on the client machine, making them relatively accessible. In contrast, session data stored on the server can be larger (tens of MB server-side if needed) and is not directly exposed to the client. This means sensitive info is usually kept server-side, with the client only holding a random session ID. Cookies can be viewed or modified by users (or malicious actors with access), while server-side sessions can be protected and typically require the session ID to access.

Dependency: Cookies and sessions are closely related, but one can exist without the other. Cookies don’t inherently require a server session; for example, a cookie might store a preference (theme=dark) with no server state. But most server-side sessions do require a cookie (or equivalent token) to link the client to the session data.

This division is important for scrapers because when you use a script (as opposed to a full browser), you become responsible for managing cookies if you want to maintain a session. A browser will automatically store and send cookies, preserving session state as you click around. A scraping script needs to do this deliberately, by using a persistent session object that stores cookies between requests.

Why Cookies and Sessions Matter for Web Scraping

Given the definitions, it’s easy to imagine why cookies and sessions are essential during web scraping, especially in certain circumstances.

In fact, not handling cookies and sessions correctly can lead to authentication failures, lost context in multi-step workflows, repeated consent walls, or quick detection by anti-bot systems. Let’s make some examples.

Authentication and Stateful Flows

Many websites require a login or maintain a user-specific state. If your scraper doesn’t manage the session, every request would appear as a new anonymous user. Using sessions allows your scraper to stay logged in across multiple requests. For example, imagine scraping a user profile page behind a login. You typically have to:

Establish a session and get a login form, for example, to do an initial GET to the login page. This often sets a session cookie (like

JSESSIONID,ASP.NET_SessionId, or a CSRF token cookie) and returns an HTML form with hidden fields (like a CSRF token).Submit credentials using the same session, POST the login form with username, password, and any required tokens. The server validates and responds with a Set-Cookie for an auth token or session id indicating you’re now authenticated.

Navigate authenticated pages and continue to use that session (cookie jar) for subsequent GET requests to pages like

/dashboardor/profile. The session cookie marks you as logged in, so you get the restricted content instead of being redirected to login.

If at any point you start a new session, you’d lose the logged-in state and likely get kicked back to the login page. While using a persistent Session object in requests, this process is straightforward: the requests.Session() will store cookies from step 1 so that steps 2 and 3 automatically include them.

The same concept applies to multi-page forms or wizards (like a 3-step checkout): sessions preserve data from previous steps. Without a session, step 2 of a form might not know what you did in step 1. Maintaining state ensures you can carry things like a cart ID, form tokens, or other context through the sequence.

Consent Gates and Cookie Banners

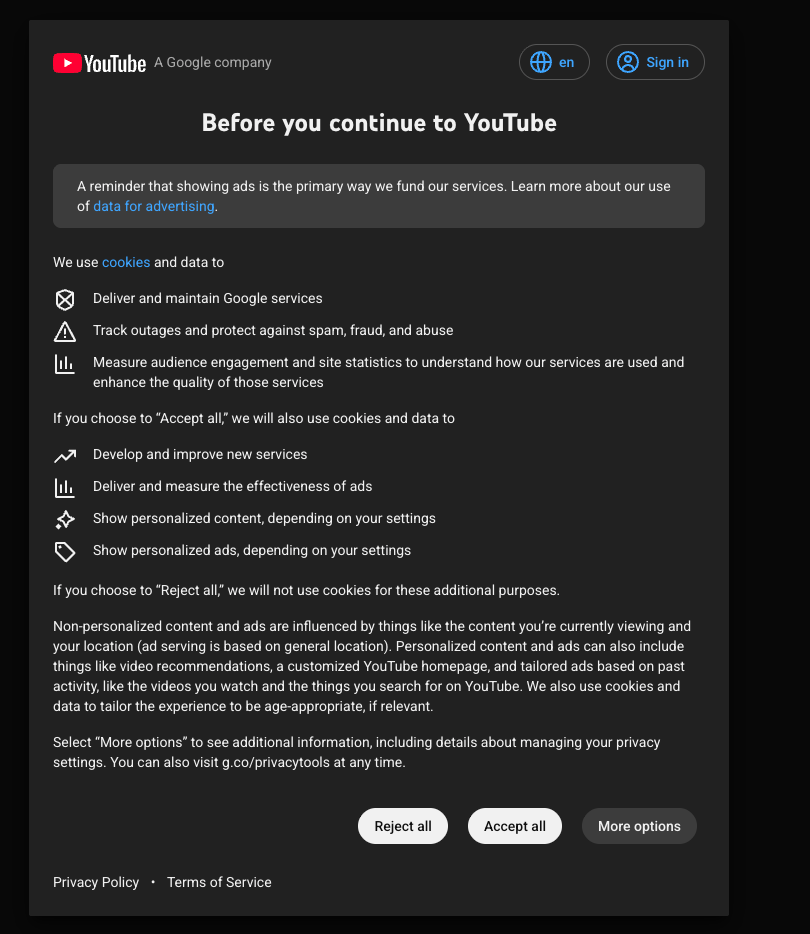

Another scenario, pretty common in Europe thanks to the cookie law, is encountering consent pages or cookie banners. For instance, scraping YouTube from a European IP will present a consent page on the first visit, requiring you to agree to cookies/terms before showing content.

If your scraper just fetches the page without acknowledging this, you’ll keep getting the consent HTML rather than the data you want. The solution is usually to simulate the acceptance of the consent, typically by setting the appropriate cookie that the site expects once the user clicks “Accept all”.

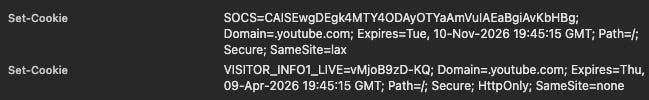

In the case of YouTube, when clicking on the “Accept all” button, you receive a Set-Cookie header in response, in particular, the SOCS and VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE ones, which will last 6 or 13 months, as the official documentation states.

In both cases, the values stored are encrypted strings, so we cannot forge them directly. However, we can use a sort of “cookie factory” that, given a browser, collects these cookies for later use by our browserless scrapers.

Before continuing with the article, I wanted to let you know that I've started my community in Circle. It’s a place where we can share our experiences and knowledge, and it’s included in your subscription. Give it a try at this link.

Anti-Bot Challenges and Tracking Cookies

When talking about cookies and sessions in web scraping, the first use case that comes to mind for professional web scrapers is, of course, related to anti-bots.

Most of the anti-bots out there use session tokens or cookies to store the state of the session, which means whether you’re allowed or not to visit that website.

Let’s see some examples.

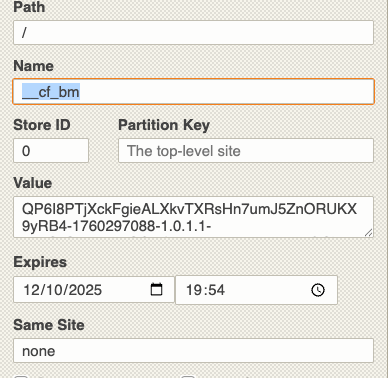

Cloudflare Bot Manager

Cloudflare uses a clearance token to indicate whether your session is valid, and, depending on the version installed, it has different names with the same prefix “cf” (cf_clearence, __cf_bm).

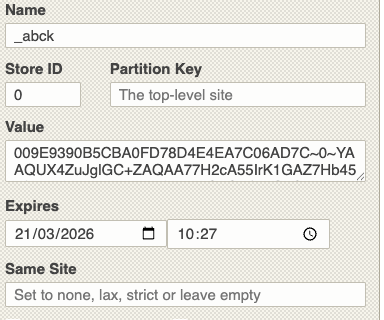

Akamai

Akamai uses the same approach by saving a cookie called _abck on the client.

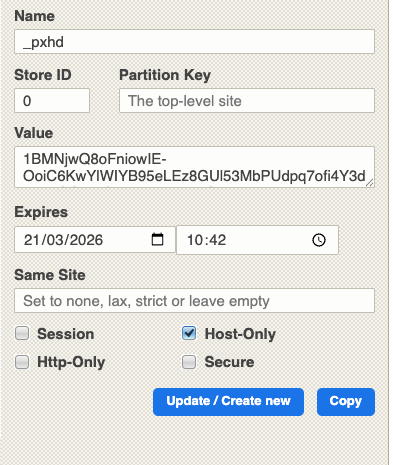

PerimeterX

PerimeterX also uses the cookie approach, using cookies that start with px, like px3 or _pxhd.

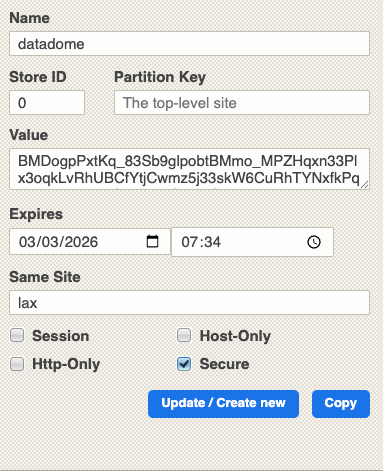

Datadome

Datadome uses cookies to store the session state, whose names are self-explanatory.

Of course, saving a cookie and reusing it could not be enough in these cases. Sometimes tokens are strictly related to a session or an IP address, so they can be used only in this specific environment, just like a normal user would do.

The scripts mentioned in this article, like the Scrapy scraper and the Camoufox one, are in the GitHub repository's folder 94.SESSIONS, available only to paying readers of The Web Scraping Club.

If you’re one of them and cannot access it, please use the following form to request access.

How to keep a session alive with HTTPX

Let’s see what happens when we use an HTTP session to make multiple requests. In Scrapy, this is the default behaviour: the whole scraper runs on a persistent session and, unless we explicitly forbid it, passes the cookies between the requests.

We can have the same features with HTTPX, a Python3 HTTP client: by using HTTPX requests, every request by default has its own session and cookies.

But if we use a Client, it will use an HTTP persistent connection, allowing us to send multiple requests and share cookies between them. Have a look at this example:

import httpx

import sys

def main():

“”“Main function - minimal version with proxy support.”“”

# Get proxy from command line argument

if len(sys.argv) > 1:

proxy_url = sys.argv[1]

print(f”Using proxy: {proxy_url}”)

else:

proxy_url = None

print(”No proxy provided - using direct connection”)

# URLs to browse

urls = [

“https://www.google.com”,

“https://www.github.com”,

“https://www.stackoverflow.com”,

“https://www.reddit.com”,

“https://www.wikipedia.org”

]

# Create client configuration

client_kwargs = {

‘headers’: {

‘User-Agent’: ‘Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_7) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/139.0.0.0 Safari/537.36’

},

‘timeout’: 30.0,

‘follow_redirects’: True

}

# Add proxy if provided

if proxy_url:

client_kwargs[’proxies’] = {

‘http://’: proxy_url,

‘https://’: proxy_url

}

# Create single client and browse all pages

with httpx.Client(**client_kwargs) as client:

print(f”\n🚀 Starting session browsing with {len(urls)} pages”)

for i, url in enumerate(urls, 1):

print(f”\n{’=’*50}”)

print(f”PAGE {i}: {url}”)

print(f”{’=’*50}”)

try:

# Make request

response = client.get(url)

print(f”Status: {response.status_code}”)

# Get cookies from client

cookies = dict()

for k, v in client.cookies.items():

cookies[k] = v

print(f”Cookies collected: {len(cookies)}”)

# Print cookies

if cookies:

print(”\nCookies:”)

for name, value in cookies.items():

print(f” {name}: {value[:50]}{’...’ if len(value) > 50 else ‘’}”)

else:

print(”No cookies found”)

except Exception as e:

print(f”Error: {e}”)

print(f”\n✅ Session browsing complete!”)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

main()

What we’re doing here is basically creating a client, sending a request to five different websites, and, after each request, we’ll print the cookies stored in the cookie jar inside the client’s instance.

A CookieJar is an in-memory data structure that:

Stores cookies as key-value pairs

Manages cookie domains, paths, and expiration dates

Automatically handles cookie parsing from Set-Cookie headers

Sends appropriate cookies with each request

At the end of the script, which you can find in the repository with the name client_test.py, you’ll have a situation similar to this one, where all the cookies from the five websites are stored in the cookiejar.

📊 FINAL SESSION STATE:

Total cookies in session: 21

Final cookie summary:

• AEC: AaJma5s3NhcajbsRb3Cb5b8pl-GttvM2rlzfSRjiza3MqDPcew...

• NID: 525=j4GtnGs0YHpD0RA_6Cnz0zFKp-wGlZ5XMZdY4WYZbPXTY3...

• _octo: GH1.1.1713835783.1760691564

• logged_in: no

• _gh_sess: lTAf8%2BvmET7J3%2FfrEPc5nIwke8FV%2FtQxrhpYVr6caOYz...

• __cf_bm: T2_zzKRmCVMwydMnNTEcQPFhIsUwrjIXG03Lz_WYHbQ-176069...

• _cfuvid: qDFlA1KF5DcODlK3ebh0v6MBSlr0YVMRt7714Xgo.pU-176069...

• prov: 1dfaa6da-676f-4d09-9c63-35c7eff4013b

• __cflb: 02DiuFA7zZL3enAQJD3AX8ZzvyzLcaG7w4XDhc9PZYX8Y

• csrf_token: 68d1ad1a2a1575183d592482e4c03b18

• csv: 2

• edgebucket: WpPQNVFgq1wlE1wnAW

• loid: 0000000020123cndq5.2.1760691570813.Z0FBQUFBQm84Z1Z...

• rdt: 64802372852dd1f22bd8075f0faee5dc

• session_tracker: irkmhojbjpalmcpdci.0.1760691570817.Z0FBQUFBQm84Z1Z...

• token_v2: eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsImtpZCI6IlNIQTI1NjpzS3dsMnlsV0...

• GeoIP: US:NY:New_York:40.71:-74.01:v4

• WMF-Last-Access-Global: 17-Oct-2025

• WMF-Uniq: gddAQkUCiP-VB2ejRLRmyQKPAAAAAFvd3AjvTlpXalALejj-Ld...

• NetworkProbeLimit: 0.001

• WMF-Last-Access: 17-Oct-2025Now that we understand how a client in HTTPx works, let’s see how we can use persistent sessions to bypass anti-bot protection in a cost-efficient way.

A real-world example: Leboncoin.fr

We understood that anti-bots usually store cookies in the browser session once they verify that your requests are from a human. We have also seen how to use HTTPX to pass cookies between different requests.

The idea behind this article is to obtain the clearance cookie from an anti-bot using a web unblocker and then use it for subsequent sessions without needing to call the unblocker again. If we’re able to make just 10 free requests for each cookie we store, we’re basically cutting our scraping costs by 90%. Not that bad.